From Fibonacci to Fidenza

by Sabrina Khan

There is an autonomous artist among us, a faceless, soulless creature, who, at the hands of talented programmers, is being employed to create seductive and thought-provoking pieces of generated art. In many ways, this autonomous machine is nothing new, having been used to create generative art since the sixties, but now, thanks to superior technologies and the explosion of this type of art in the digital art landscape, questions arise as to whether or not generative art can rank alongside the masterpieces of traditional great art.

As generative pieces are created by artists like Tyler Hobbs, who dazzled the art scene with his Fidenza collection, we are left in the afterglow with many questions, the answers of which will shape the trajectory of generative art: is the computer the artist or is the artist the one who feeds the computer the custom created algorithm? Is art rendered by a machine true art? Can this generated art move us and evoke the same emotions affected by traditional paintings?

Opinions will differ, but due to the presence of mathematically rendered elements within both nature’s beauty as well as in great masterworks of traditional painters, there is something innately within us that appreciates and is affected by these renderings, suggesting that our relationship to generative art is a natural one, and our acceptance of it as true art is essential.

We Are All in Love With Fibonacci

Our relationship to mathematically rendered beauty goes back to the year 1202, when Leonardo Pisano Bigollo sojourned one sultry summer through the Middle East and was captivated by mathematical ideas that had come from India. Dizzied with numbers, he went home to Italy and wrote one question:

“If a pair of rabbits is placed in an enclosed area, how many rabbits will be born there if we assume that every month a pair of rabbits produces another pair, and that rabbits begin to bear young two months after their birth?”

This innocuous question gave birth to the Fibonacci sequence: 0, 1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, 21…where the next number is found by adding up the two numbers before it and so on forever. Consequently, this startling sequence spiraled into the far depths of mathematics and computer science, but also, into the world of nature and art.

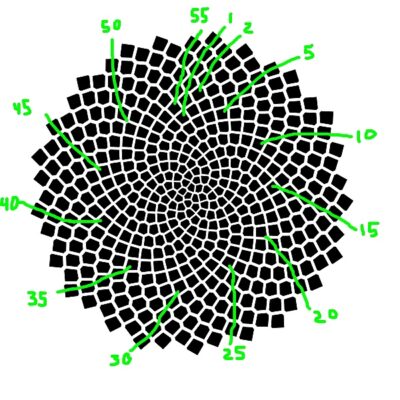

Scientists and mathematicians alike were baffled to find that this very same sequence was in operation within nature itself. In an orchard, choose any tree, elm, cherry, beech, poplar, weeping willow, twist a branch in your hand, count the leaves and the number of turns it takes along the branch all the way back to the one directly above the original leaf. Both numbers will be from the Fibonacci sequence. Find Fibonacci in a sunflower.

Sunflower (source)

55 Spirals (source)

At its core, the golden ratio is resplendent, featuring 55 spirals going in one way, 89 in the other. This pattern is ubiquitous, in the nature we see, the hurricanes from which we flee, the shells on the beach. It exists within us in our DNA strands and in the cochlea of our inner ear, and even beyond in the glittering construction of the spiral galaxies and Milky Way. Nature employs this perfect mathematical sequence and we are enamored by the results.

Da Vinci and Dali Join The Fibonacci Fest

Inspired by nature’s mathematically achieved beauty, master artists saw the sequence as a muse for their works. In 1495, Leonardo Da Vinci painted a mural for the church that would convey the exact moment when Jesus announced that one of his apostles would betray him: “The Last Supper.”

Once of Da Vinci’s most celebrated works, famed for capturing a cornucopia of human emotion at the very zenith of a religious turning point, the piece has captivated audiences for centuries and has been hailed as a perfect painting. In fact, it is perfectly rendered as the architecture shows golden ratios in abundance throughout the work, as the table, ornamental shields, windows, and position of the disciples to Jesus all follow the Divine Proportion.

The painting features the numbers of the Fibonacci series: one table, one Jesus central figure, two walls, three windows with three figures in three groups, figures in five groups, eight wall panels, eight table legs, and overall thirteen individual figures. This perfect mathematically rendered and proportionate piece speaks to our minds and to our souls, for there is something innately within us that responds to this symmetry, both in nature and in the artist’s creation.

Last Supper, Leonardo Da Vinci (source)

Indisputably, there is a relationship between nature and mathematics, between the things we perceive beautiful and the way in which they are sequentially generated by the finite control and constrictions of numbers. Da Vinci employed the Fibonacci sequence in 1495 and Salvador Dali explored it in 1949.

Dali understood this relationship and wrote in his book 50 Secrets of Magic Craftsmanship:

“You must, especially as a young man, use geometry as a guide to symmetry in the composition of your works. I know that more or less romantic painters argue that these mathematical scaffolds kill the artist’s inspiration, giving him too much to think and reflect.”

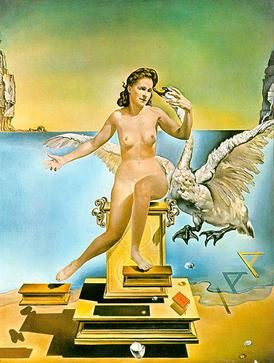

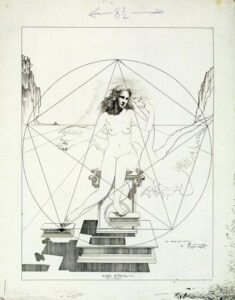

In “Leda Atomica” Dali uses the divine proportion to set Leda and the swan within a pentagon calculated with the golden ratio.

Leda Atómica (Atomic Leda), Salvador Dalí, 1949

Studies of Leda Atómica, 1947

Dali believed that mathematical equations and carefully calculated renderings, when merged with artistic creativity, could create glorious artforms. A set of numbers and equations set by nature can produce a sunflower, the mathematical calculations of proportions and ratio produces “The Last Supper”, and today, the algorithmic input given to a computer can achieve a masterwork of artistic creation, like Fidenza.

Falling for Fidenza, an Inevitable Love Story

Generative artist and coder Tyler Hobbs understands the relationship that is at the heart of our love of mathematically rendered design, as he begins his art process by developing an algorithmic code for his generative pieces. Of his codes, he states:

“Often, these strike a balance between the cold, hard structure that computers excel at, and the messy, organic chaos we can observe in the natural world around us.”

This idea is brought to fruition in his magnificent Fidenza collection. Hobbs employs flow fields to create his pieces, and has unlocked the ways in which they produce an endless and unpredictable array of curves, turns, and spirals. In each piece, there is a sense of continuation, eternity captured on canvas, as if somehow the continual loop of forever was bottled and stored by the artist for the enjoyment of the collector.

This same feature is found in the pearlescent structure of nautilus shells, giving these specimens a riveting appearance of embodying the very shape of eternity. Furthermore, it is no coincidence that this sense of eternity captured by mathematics was what Da Vinci used to convey a timeless tale of immortality and eternal faith in his most revered painting.

As mortals, we share a connection to this sense of eternity, given that we are each a component within the continual life flow of existence. This visual eternity is celebrated in Fidenza, as with a masterful manipulation of scale, an endless array of generative possibilities are the outcome, some surprising, some startling.

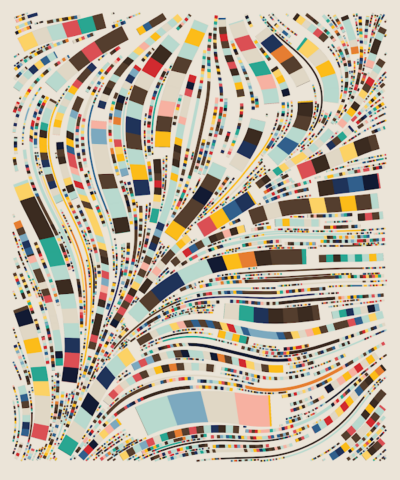

In Fidenza #313, The Tulip, this sense of eternity and infinity is celebrated in the blooming arms and gentle curves of rectangles resplendent in proportioned perfection. Varying in color, shape, and size, these shapes travel endlessly, caught in an infinite loop of life and death and rebirth.

Fidenza #313, “The Tulip”

The same awe-inspiring elements that entrance us when we dream of spiral galaxies and wander through labyrinths are captured in nearly all Fidenza pieces, but most notably in The Tulip, affirmed by punk6529:

“I believe Fidenza #313 (The Tulip) is among the very very very most definitive Fidenzas. By extension, The Tulip is one of the most important pieces in Art Blocks history and, further, in early on-chain generative art. Time will tell if history agrees with me.”

Hobbs Blazes the Trail for Generative Art

For many decades, generative art has been a secret pastime of programmers, not a form that has been embraced by the art community or seen as true art, due to its technical conception. It is easy to dismiss its lack of emotional value because the artist who creates it sits distantly from the subject, entering code to produce it, rather than using brushes or digital pencils.

Though Da Vinci and Dali were not creating generative art, strictly speaking, they were generating pieces that were constricted by mathematical equations which bound the parameters of the art, similar to the ways in which computer algorithms do for generative pieces. Nevertheless, Da Vinci and Dali may have employed mathematical equations, but in the end they tangibly held the brushes that enchanted the canvas with the images that are immortal in our collective memory.

Anything that deviated from this method was not viewed as true art, and sometimes still meets resistance. Hobbs challenges this tradition with his tremendously moving and glorious pieces. Fidenza is the progeny of perfect programming and the artist’s sensibility. Through his art, Hobbs proves that emotion can be evoked by generated pieces if the artist maintains a sense of what is moving and what is enduring when creating the code and producing the art.

Hobbs states: “That is the moment when the artwork must succeed. If an intimate relationship between the viewer and the artwork is not established here, nothing else matters.” It is his mission as a generative artist to create this connection between art and viewer, when the art has been created via a computer program with his algorithmic instruction.

Furthermore, it is a step toward cementing generative art within the canon of great art, allowing something rendered by a machine to evoke within us the same soul shifting effects that traditional art can.

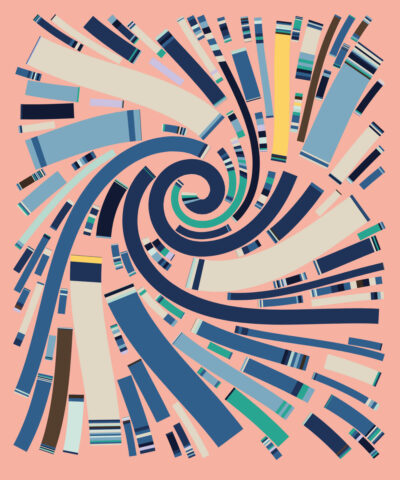

Fidenza #938, “God Mode”

Fidenza #772

Marriage of Man and Machine

Our love of this kind of art is already innate, as we are enamored by the mathematical sequences that nature has generated for us: perfectly spaced disc florets at the heart of a sunflower head, the perfectly positioned hands of Da Vinci’s Jesus placed within the golden ratio triangle of his form, and the sumptuous, elegant curves of Fidenza pieces.

We are predisposed with an inherent love for a mathematically perfect rendered element, and that is why there is already a deep connection between that which is computationally rendered and that which is artistically beautiful and admired. To find that balance is to find the key to unlocking exquisite art and to usher in generative art as a new kind of art that can hold its place amongst the greats.

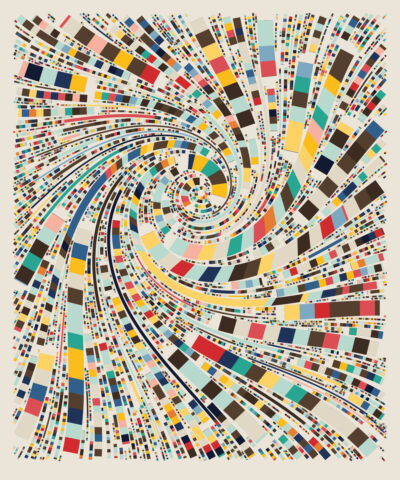

Fidenza #612

For the soulless autonomous computer, Hobbs is its soul, as all artists must be, breathing life and emotion into these digital renderings. With his creation of a code and his imagined vision of various traits, textures, colors, spatial organization, he inspires the machine to generate all of the possible versions. Sometimes it is what he expects, sometimes it is surprising. In this way, generative artists create a marriage between man and machine to create meaningful and moving works of art.

As our world exists more and more on a digital landscape, it is essential that as we embrace the outputs from our exemplary and powerful technology, we impress upon it our humanity.

Liked this article? Don’t forget to check out A Tale of Two Artists: Van Gogh and XCOPY!